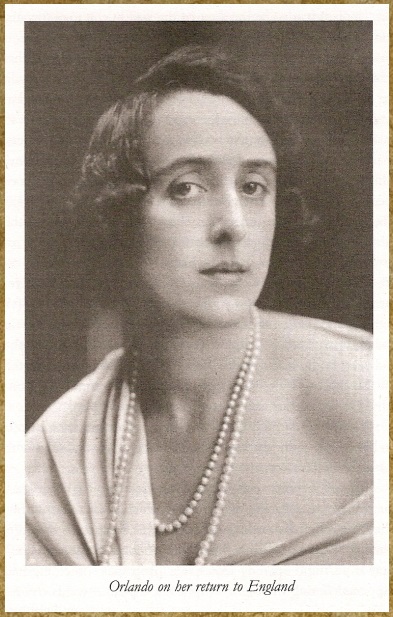

Orlando, orlando, orlando. Could there be a more exhilirating account of the writer’s life?

From the opening line Woolf announces the freewheeling narrative style she intends to adopt in her whimsical, slightly off “biography” of the Elizabethan aristocrat Orlando (a stand-in for Woolf’s lover Vita Sackville-West) who is constrained by nothing: not time, or sex, or tradition, in a majestic critique of biography, fact, and societal “norms.”

Orlando (and Woolf’s subversive writing style, in all of its breaking of the fourth wall and sly jabs at the dominant male voices of the age) was a modernist before his time. A solitary wanderer, an amateur poet, royalty. A boy who despite his position, finds himself perpetually shifting between emotional extremes, riding high on life only to fall into the depths of despair. Why? Orlando is a writer. And embedded in a raucous adventure story masquerading as biography, we find Woolf is documenting nothing other than the life of a writer, long before we as a culture spent countless words analyzing said life. And who better to lay it out? Woolf knew it, in all of its self-doubt and contradiction, all too well.

“Anyone moderately familiar with the rigours of composition will not need to be told the story in detail; how he wrote and it seemed good; read and it seemed vile; corrected and tore up; cut out; put in; was in ecstasy; in despair; had his good nights and bad mornings; snatched at ideas and lost them; saw his book plain before him and it vanished; acted people’s parts as he ate; mouthed them as he walked; now cried; now laughed; vacillated between this style and that; now preferred the heroic and pompous; next the plain and simple; now the vales of Tempe; then the fields of Kent or Cornwall; and could not decide whether he was the divinest genius or the greatest fool in the world.”

Woolf (seemingly forever tongue-in-cheek) describes Orlando’s love of literature as a disease, an infection, which grows in solitude and leads to an even worse disease – writing. When Orlando catches it, he literally loses years.

Because of course, as only a writer can know, and as only a writer can dictate, life is not constrained by time.

“Life seemed to him of prodigious length. Yet even so, it went like a flash.”

Orlando is a fantasy novel. In a way. For Orlando is not tethered to time (or anything else for that matter): he falls asleep for days, wakes up in a new century, wakes up a woman. Because why not? “The extraordinary discrepancy between time on the clock and time in the mind is less known than it should be and deserves fuller investigation,” Woolf writes as a biographer’s aside. “The true length of a person’s life…is always a matter of dispute.” Does it not live on, on the page anyways, indefinitely?

Orlando wallows in the benefits of obscurity and despairs of discovering truth. Words come when she least expects them, when it would be “impossible” for them to appear, and fail him when he tries. She is entranced with the world and sick of it in equal measure. She is on a perpetual rollercoaster between the need for solitude and the desperate craving for companionship, romantic companionship particularly.

“I have sought happiness through many ages and not found it; fame and missed it; love and not known it; life — and behold, death is better. I have known many men and many women, none have I understood.”

As some know only too well, brilliance comes only when it is least expected. When Orlando becomes neither submissive to, nor combative of, life and her age, only then can she write. And she writes and writes and writes.

Of course Woolf also offers herself, in the guise of the biographer, as an exemplar of the writing life. “Thought and life are as the poles asunder,” her biographer declares. So when Orlando sits, there is nothing for the biographer to describe, “life, the same authorities have decided, has nothing whatever to do with sitting still in a chair and thinking.”

The great paradox of writing. Something others have written about far more beautifully than I: “One can never be alone enough to write” (Susan Sontag), the need for, and hatred of, solitude. The need to be of the world and at the same time to be apart from it.

“What is more humiliating than to see all this dumb show of emotion and excitement gone through before our eyes when we know that what causes it— thought and imagination—are of no importance whatsoever?” Woolf facetiously asks, poking a zillion holes in the historian and encyclopedist’s sorry attempts at documentation. It’s not facts that matter silly, she seems to be saying, thought and imagination are the only things that matter.

Orlando concludes abstractly, but before Orlando buries her manuscript near the oak tree which inspired her lifetime spent in search of truth, a life spent writing, she feels the insatiable desire to have her work read. And read it is, leaving Orlando with a giant weight lifted, a weight he/she has carried with her, as we all have, throughout the tortuous writing process.

By freeing Orlando of any and all constraints, and any and all absolutes, Woolf has provided her readers with the most gloriously liberating, entertaining, and enlightening account of the writer’s life anyone had seen up until that point (or, I would argue, will ever see again). Orlando is of course about much more than writing, but writing, for many of us, is life.