“Dada was born of a need for independence, of a distrust toward unity. Those who are with us preserve their freedom. We recognize no theory.”

Or so declared Tristan Tzara in his Dada Manifesto of 1918, ushering in an era of anti-art and art as a method of protest.

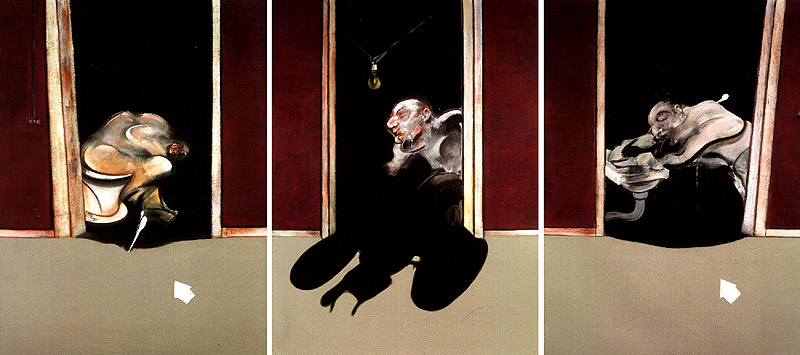

When Dada was born the idea of an anti-art, second nature to us now, could not have been more shocking.

)As an aside, it’s not easy to imagine anything in art falling under the label of “shocking” ever again? Disappointing.)

Nevertheless, for the society of the early 20th century, Dada was shocking, and the ideas it spawned; art as protest, humor in anti-art, the intention to shock and a post-modern refutation of tradition and standards, would spawn many similar and similarly shocking art movements over the next century.

One in particular, one of the more interesting and either most accessible or least depending on how you look at it, was Fluxus.

While on the surface the group appeared radical, I posit they were simply picking up where Dada left off and formulating an artistic language for a new generation, a generation, which struggled with how to react to the massive technological and political upheavals that were happening all around them.

So what is Fluxus? And how does one defend the practice of eating salad as art?

Fluxus was born in the 1960’s without a unifying statement or clear direction.

Despite George Brecht’s (a founding Fluxus artist) rejection of a credo as central to Fluxus’ identity, several other founding artists attempted to create one anyways, albeit a very untraditional one. The most well known declarations were those of George Macinuas who wrote Fluxus Manifesto’s one and two.

In Manifesto I, which Maciunas authored in 1963, the three core principles of Fluxus, at least as Macinuas perceived them, were established. Taking as a starting place the dictionary definitions of three central words and adapting them to his purposes, Macinuas elucidated Fluxus thusly (abbreviated):

- Purge the world of the “intellectual” and commercial culture. Purge the world of dead or illusionistic art.

- Promote living, anti and non-art which can be grasped by all people

- Fuse the cadres of all revolutionary groups into one

It was to be a rejection of everything he and his contemporaries viewed as standard and accepted, as well as an incitement to cultural revolution.

Fluxus, just as Dada before it, spurned the notion of acceptance and strove to create a counter-culture.

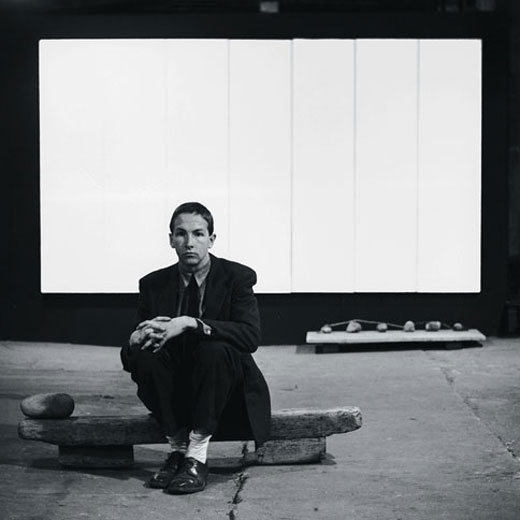

The loose group which assembled under the name of Fluxus was made up of many artists. George Brecht, George Macinuas, Dick Higgins, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik and Allison Knowles to name a few. They were the Neo-Dada in their conscious attempt to disrupt normalcy.

Fluxus art was a great many things but above all, it was action based. Performances were central to the Fluxus artists. New media was also essential. The Fluxus artists explored the use of electronic music and film extensively and very little ‘traditional’ art was categorized under the name due to its conscious reactionary stance against the mediums of the ‘system.’

Due to the temporary nature of the group’s most famous medium, the happenings or performances, much of what we know of Fluxus art is in the form of descriptions. Descriptions of what sounds like little more than organized chaos.

Fluxus was inaugurated, for all intents and purposes, at the first official Fluxus event in Wiesbaden, Germany. The event was called Festus Fluxorum and was organized by Maciunas. Participants included Knowles, Higgins, Brecht and Paik among others.

I won’t give a full account of the ‘performance’ but here is a taste.

Four men stand behind a table in formal suits rhythmically clapping their hands. One man blows a kazoo. Knowles forcefully sits down then stands up. Wooden blocks are smashed. Paik plucks a violin. Paik paints with his hands. Paik spits tomato juice onto a canvas. Knowles repeatedly shouts “Never, never” while another reads incomprehensible statements from a book.

I could go on.

Fluxus was born.

Fluxus movements occurred throughout the world in the aftermath of the Wiesbaden birth, and many artists grouped themselves under the conceptual umbrella of these “revolutionaries.”

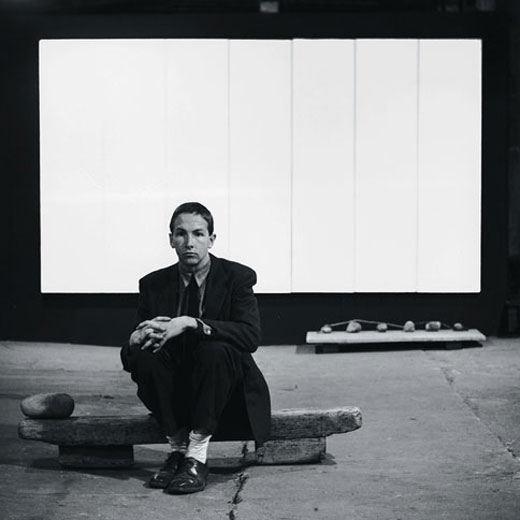

One of the more famous, and actually remaining Fluxus works, was Paik’s “Zen for Film.” 23 minutes of nothing, blank film, often considered to be the first example of video art.

In my headline I alluded to a Fluxus performance by Knowles called Proposition. In the piece, performers go through the steps required to create a salad; cutting the vegetables, assembling the dressing, etc.

Another example of a Fluxus performance is Ono’s Cut Piece, in which she invited members of the audience to cut away pieces of her clothing.

Suffice to say, Fluxus art could be anything provided it was governed by a general lack of structure, a calling of attention to the daily or mundane and demonstrated an overall lack of ‘skill.’

Examples abound but the idea of the performances is really summed up in my detail of the Festus Fluxorum. They weren’t, contrary to what you might suppose, random events, but actually carefully choreographed acts. Fluxus work could take innumerable shapes; a book, videos, combinations of multiple media, etc.

It’s weird, it’s nonsense, but say what you will, the movement is an important part of art history so it’s impossible to ignore.

I’m inclined to think Dada got it right and Fluxus took what is really an interesting notion to the point of no return, at least apart from legitimizing nonsense in art for a whole generation of artists to follow. A legitimization which would be unabashedly abused.

I’ll come back to me in a minute, but first, here are some ways Fluxus artists attempted to translate and elucidate their work to the public.

Dick Higgins said of Fluxus that it was “not a moment in history, or an art movement. Fluxus is a way of doing things, a tradition and a way of life and death.”

Fluxus artists touted their art actions as attempts to imbue the ordinary with meaning. By transforming things like sleeping, making/eating dinner and jumping into art, those things themselves became art, in their opinion. It’s kind of abstract but hopefully you follow. Intention is, after all, what sets art apart from the ordinary in this century.

Fluxus artists strive for a lack of structure, they wanted their undiluted concentration to be the only thing keeping their art from being nothing more than random chance.

In the words of Fluxus artist Allan Kaprow on his happenings, it was time to move into the art, instead of just looking at it. Art should consume your time and fill an environment, something a mere painting could rarely do.

As mentioned earlier with Macinuas’ Manifesto, the Fluxus artists were reacting to an art world dominated by the elite and the intellectual and their nonsense and talentless work was their preferred method of revolution; the elimination of the professional in art.

Bringing modern art to a less elevated level is a noble aim, but by reducing art to nonsense, is that really what you’re accomplishing? Or are you simply altering the meaning of art, something that seemingly, or at least should, by definition implies a skill or talent?

In Macinuas’ Manifesto II, his “Fluxmanifesto on Fluxamusement” he attempts to do that very thing. Maciunas states the artist must demonstrate his own dispensability. “He must demonstrate that anything can substitute art and anyone can do it…Amusement must be simple, amusing, concerned with insignificances, have no commodity or institutional value…It must be unlimited and eventually produced by all.”

The second manifesto was a harsher reaction to the art world while also a defense of Fluxus as non-serious art, something anyone who had already seen a performance would have deduced. It reaffirmed the importance of the general public to Fluxus art as well as the self-sufficiency of the audience. They too could perform what the ‘artists’ were performing.

It was the notion of anyone as artist that most likely contributed to a decline in Fluxus practice. Rampant “performances” and “happenings” caused the idea to lose originality and fade into obscurity as it was impossible for the public to distinguish between the serious practicioners and the frauds.

One defense of the movement more valid than most others, is the centrality of Buddhist thought to the Fluxus practicioners.

Ellen Pearlman delves into the Eastern religion’s influence on the movement in great depth in her study Nothing and Everything.

Knowles, when speaking of her performances often used Buddhist terms for meditation practices and an idea central to the Eastern religion is the lack of a duality, an idea which Fluxus embraces in it’s attempts to make art both serious and not-serious.

There is a definite meditational quality to much of the work that was created by the artists which on the surface appears pointless and boring. Paik’s “Zen for Film” for example, could be nothing, or it could be an intentional calling of attention to the pieces of inert matter that naturally fall onto a camera or backdrop, mimicking the activity of the blank mind in meditation.

It, just like Buddhism, sought to find and accentuate the value of the ordinary. To eliminate commodification and highlight individual experience. To embrace opposition and formulate and live an active philosophy of existence.

Artists who caused the notions of Buddhism to be central to their art insured that their art “sidestepped aesthetics through the act of immediacy and the inability to erase or second-guess one’s moment of creation.” (Ellen Pearlman, Nothing and Everything)

In Buddhism, art is an integral part of life and for Fluxus artists, the paramount aim was that art would resemble life. Therefore in their art, as in life, once a decision was made, it was final.

Again, all noble aims.

You can see where I’m going with this.

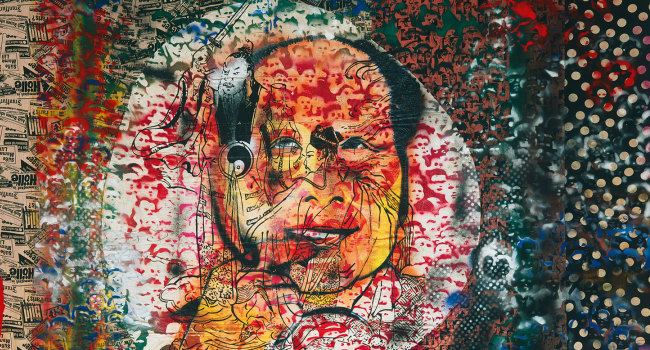

I recently read Jed Perl’s dissection of Ai Wei Wei as an artist in The New Republic, an essay in which Perl states Wei Wei has “no particular aptitude for art.” Despite the fact that the man is currently a subject of a solo show at the Hirshorn and has works in museums from the Tate to the Metropolitan.

As anyone who knows me is well aware, I am in a constant struggle with how to rationalize my love, or lack of love, for an artist or a style with his/her/it’s place in art history. In Perl’s piece I found some much needed confirmation that it is indeed okay to disagree on art.

Which is exactly where I stand with Fluxus.

The intention was noble and the reactionary stance understandable. The method is what loses me.

We will always want to react against the establishment. It’s in the nature of people, especially young people. Tumultuous times exacerbate the need and as everyone knows the 1960’s and 1970’s were enigmatic decades. The Fluxus artists were asserting independence from a world they didn’t understand, run by people to whom they could not relate.

If only they could have taken some of their worthwhile notions such as independence, individuality and the desire to allow everyone, not just the elite, access to art, and created a valuable method of expression and communication.

What we were left with instead was a group of people who wanted change but lacked a vision for what that change should be. Instead they floundered in a sea of nonsense, random acts and spectacle.

It was an art that didn’t make sense for a time that didn’t make sense but while attempting to express the feelings of a generation, I believe it served to devalue the very notion of art. While gaining a place in art history due in large part to it’s novelty and it’s philosophical similarities to Dadaism, Fluxus leaves much to be desired.

Tzara sought above all the preservation of an artist’s freedom. The Fluxus artists chose to capitalize on their relatively new freedom without explicating a clear and challenging vision concerning their intention.